Routine immunisation, extraordinary impact: Rubella

- Impact

- Routine immunisation, extraordinary impact: Rubella

Routine immunisation, extraordinary impact: Rubella

25 April 2023

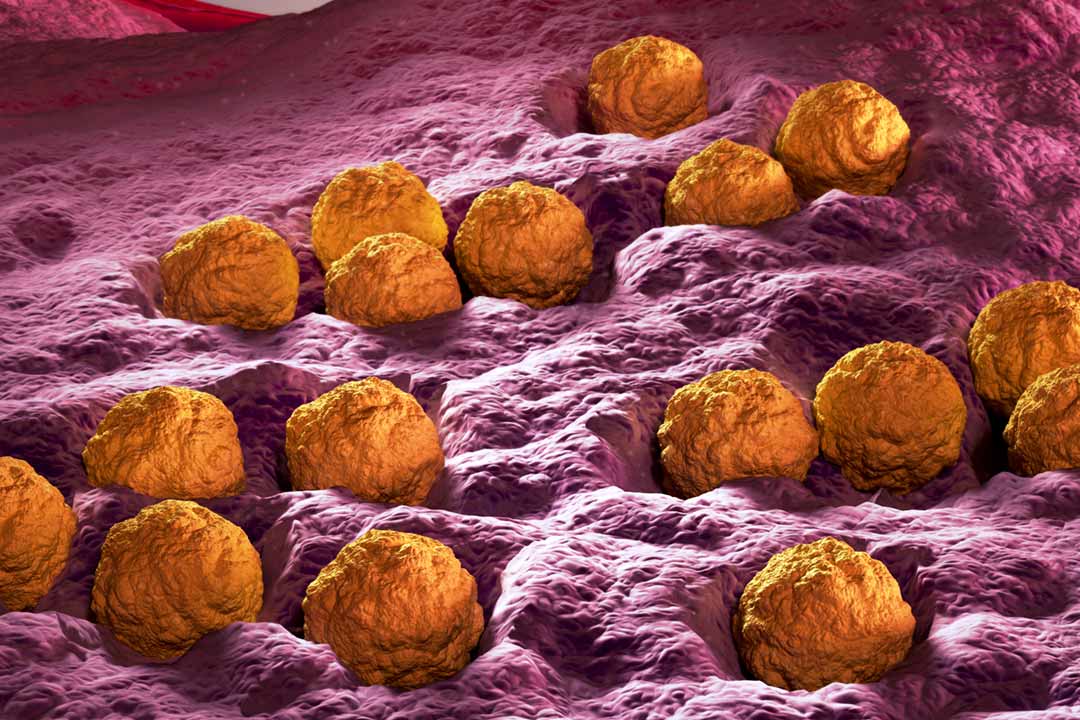

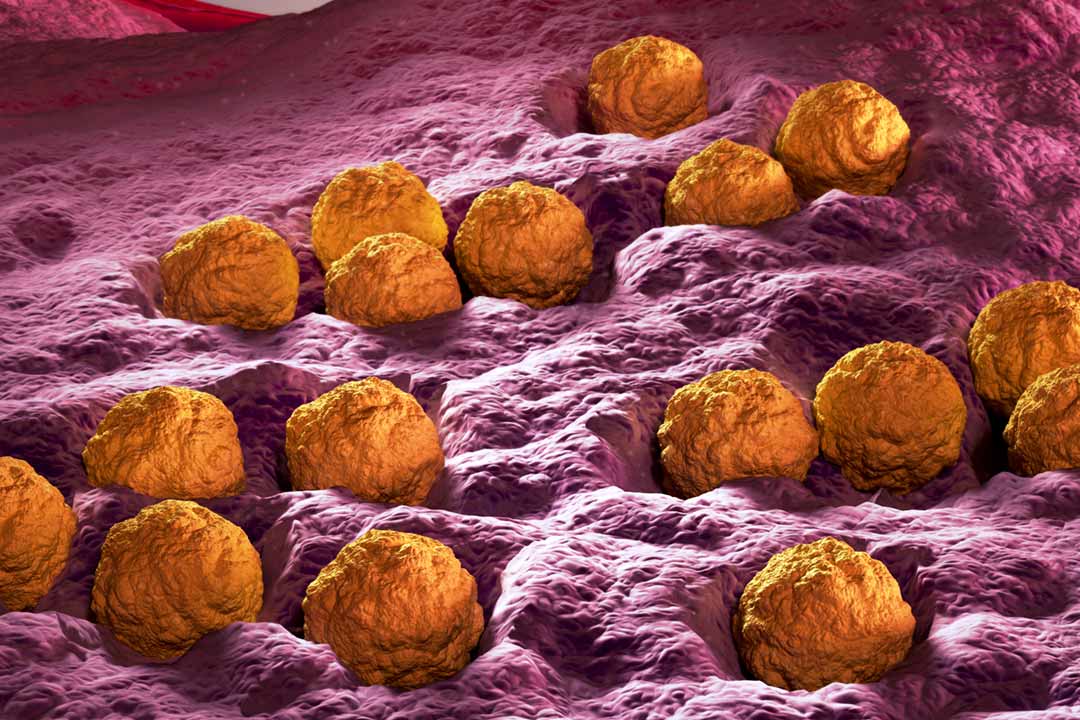

Rubella virus

Rubella can severely affect babies in the womb, leading to birth defects including heart problems and loss of hearing and eyesight. Yet even though it can be prevented by immunisation, many low-income countries don’t have enough vaccine coverage to stop the spread of the virus.

Rubella can severely affect babies in the womb, leading to birth defects including heart problems and loss of hearing and eyesight. Yet even though it can be prevented by immunisation, many low-income countries don’t have enough vaccine coverage to stop the spread of the virus.

By Gavi Staff

Announcements

IFFIm impact: rubella

IFFIm has disbursed more than US$ 37 million to Gavi's life-saving measles-rubella programmes.

For more than 200 years, the origin of the rubella virus remained a mystery, a "lone wolf" pathogen and the only member of its family (Matonaviridae) and genus (Rubivirus). This was until early 2019, when teams in the US and Germany independently discovered the first near relatives of rubella virus.

The US team were studying coronaviruses in bats in Uganda and found ruhugu virus (RuhV) – closely related to rubella – in 50% of the bats. Meanwhile, near the Baltic Sea in Germany, mysterious cases of acute neurologic disease at a zoo affecting first a donkey, then a tree kangaroo, then a capybara, led to an investigation which led to the discovery of rustrela virus (RusV), the second-nearest neighbour to rubella virus.

So far there is no evidence that either ruhugu or rustrela viruses can infect humans, , or that rubella virus can move in the opposite direction from humans to infect animals. However, the rustrela virus can jump between species even as distantly related as placental and marsupial mammals, which for the first time hints at the possibility of a zoonotic origin for the rubella virus.

Rubella-infected pregnant women have a risk as high as 90% of miscarriage, or their baby dying in the womb. Even when babies live, they can develop congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) which can mean serious birth defects.

Rubella was first described in 1740 by German physician and chemist Friedrich Hoffman as causing distinctive reddish-pink marks. It picked up the name German measles (or 'Röteln' as Rötlich means "reddish" or "pink" in German)although rubella and measles are not related.

In 1814, George de Maton suggested that it be considered a disease distinct from both measles and scarlet fever. Later, Henry Veale, an English Royal Artillery surgeon, described an outbreak in India, coined the name "rubella" (from the Latin word, meaning "little red") in 1866.

Threat to lives

Rubella is an acute infection that is incredibly contagious and spreads twice as easily as SARS-CoV-2.

According to the World Health Organization, rubella is seasonal and in temperate zones, for example, is most often seen during the late winter and spring, with epidemics every five to nine years. However, the extent and periodicity of rubella epidemics is highly variable worldwide, and the reasons are still not clear.

Symptoms in children tend to be mild and include low-grade fever, respiratory problems, and most notably a rash of pink or light red spots that usually begins on the face and spreads downward. The rash occurs about two to three weeks after infection. Swollen lymph glands behind the ears and in the neck are a characteristic feature of this infection. Adults, especially women, are more likely to experience complications from rubella including arthritis and encephalitis.

A single dose of the rubella vaccine gives more than 95% long-lasting immunity. Before the introduction of the rubella vaccine, as many as four babies in every 1,000 were born with CRS.

However, the most serious complications from rubella infection come when unvaccinated pregnant women become infected and pass the virus on to their developing babies.

Rubella-infected pregnant women have a risk as high as 90% of miscarriage, or their baby dying in the womb. Even when babies live, they can develop congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) which can mean serious birth defects including heart problems, loss of hearing and eyesight, intellectual disability and liver or spleen damage.

Although routine immunisation has reduced or eliminated rubella in high-income countries, it remains a public health concern in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where more than 100,000 children are born with CRS each year.

Vaccine development

There is no treatment for rubella infection, so vaccination is critical in preventing the devastating outcomes it can result in. Women who plan to become pregnant, but who do not have sufficient levels of antibodies to the virus, can take a rubella-containing vaccine 28 days before conception.

Rubella virus was first isolated in 1962 by two independent groups, Paul Parkman and colleagues, and Thomas Weller and Franklin Neva.

Work on a rubella vaccine began in earnest after the US was hit by a devastating epidemic in 1964, during which around 12.5 million people got rubella, 11,000 pregnant women lost their babies, 2,100 newborns died and 20,000 babies were born with CRS.

Most modern rubella vaccines contain the RA 27/3 strain developed by Stanley Plotkin and Leonard Hayflick at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia.

A single dose of the rubella vaccine gives more than 95% long-lasting immunity. Before the introduction of the rubella vaccine, as many as four babies in every 1,000 were born with CRS.

The vaccine is given in two doses, and while it is available as a standalone rubella immunisation, typically it is given to children in combination with measles or measles and mumps vaccines.

Continued threat

When there is a low level of childhood immunisation in a population it is possible for rates of congenital rubella to rise as more women make it to child-bearing age without either having been vaccinated or exposed to the disease. Therefore, it is important for more than 80% of people to be vaccinated for the population to have robust protection.

Like measles, rubella is a disease that is almost completely preventable by vaccination and it's cheap – two recommended doses of measles and rubella vaccine cost less than US$ 2 per child – yet rates of immunisation with rubella-containing vaccine have been slowly decreasing in countries with previously high coverage, such as the US.

Progress in boosting rubella vaccination rates worldwide has been patchy – rates of CRS are highest in the WHO African and South-East Asian regions where vaccination coverage is lowest.

As a way to increase the focus, the Measles Initiative set up in 2001 has now become the Measles & Rubella Partnership, which is fully aligned with the Immunization Agenda 2030, of which Gavi is also a member.

Getting vaccines out to countries that need them will be critical, as will better communication to overcome any potential vaccine hesitancy that might be leading to lower routine immunisation rates.

|

This article is republished from VaccinesWork under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. VaccinesWork is an award-winning digital platform hosted by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance covering news, features and explainers from every corner of global health and immunisation. |

Share this article

Restricted Access Library

The material in this Restricted Access Library is intended to be accessed only by persons with residence within the territory of a Member State of the European Union and is not intended to be viewed by any other persons. The material in this Restricted Access Library is provided by IFFIm for information purposes only and the materials contained herein were accurate only as of their respective dates. Certain information in the materials contained herein is not intended to be, and is not, current. IFFIm accepts no obligation to update any material contained herein.

The material in this Restricted Access Library is intended to be accessed only by persons with residence within the territory of a Member State of the European Union and is not intended to be viewed by any other persons. The material in this Restricted Access Library is provided by IFFIm for information purposes only and the materials contained herein were accurate only as of their respective dates. Certain information in the materials contained herein is not intended to be, and is not, current. IFFIm accepts no obligation to update any material contained herein.

Persons with residence outside the territory of a Member State of the European Union who have access to or consult any materials posted in this Restricted Access Library should refrain from any action in respect of the securities referred to in such materials and are otherwise required to comply with all applicable laws and regulations in their country of residence.

By clicking Access restricted content: DYNAMIC-LINK-TEXT I confirm that I have read and understood the foregoing and agree that I will be bound by the restrictions and conditions set forth on this page.

The materials in this Restricted Access Library are for distribution only to persons who are not a "retail client" within the meaning of section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 of Australia and are also sophisticated investors, professional investors or other investors in respect of whom disclosure is not required under Part 6D.2 of the Corporations Act 2001 of Australia and, in all cases, in such circumstances as may be permitted by applicable law in any jurisdiction in which an investor may be located.

The materials in this Restricted Access Library and any documents linked from it are not for access or distribution in any jurisdiction where such access or distribution would be illegal. All of the securities referred to in this Restricted Access Library and in the linked documents have been sold and delivered. The information contained herein and therein does not constitute an offer for sale in the United States or in any other country. The securities described herein and therein have not been, and will not be, registered under the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the "Securities Act"), and may not be offered or sold in the United States except pursuant to an exemption from, or in a transaction not subject to, the registration requirements of the Securities Act and in compliance with any applicable state securities laws.

Each person accessing the Restricted Access Library confirms that they are a person who is entitled to do so under all applicable laws, regulations and directives in all applicable jurisdictions. Neither IFFIm nor any of their directors, employees, agents or advisers accepts any liability whatsoever for any loss (including, without limitation, any liability arising from any fault or negligence on the part of IFFIm or its respective directors, employees, agents or advisers) arising from access to Restricted Access Library by any person not entitled to do so.

"Relief" for mothers in Bayelsa state as malaria vaccine makes waves

07 November 2025